Nikki Garcia and Brie Garcia never have to look twice to find a shoulder to lean on.

“Sisters are a very special thing, and then what’s double that is when you’re an identical,” Nikki said on a...

Nikki Garcia and Brie Garcia never have to look twice to find a shoulder to lean on.

“Sisters are a very special thing, and then what’s double that is when you’re an identical,” Nikki said on a...Source: E! Online (US) - Top Stories | 21 Nov 2024 | 6:00 am

We Included these products from Madison LeCroy because we think you'll like her picks. Madison is a paid spokesperson for the Amazon Influencer Program. E! may get a commission if you purchase...

We Included these products from Madison LeCroy because we think you'll like her picks. Madison is a paid spokesperson for the Amazon Influencer Program. E! may get a commission if you purchase...Source: E! Online (US) - Top Stories | 21 Nov 2024 | 6:00 am

Once upon a time, a princess found herself in New York City.

That was the simple but irresistible premise of 2007's Enchanted, which proved to be a star-making role for Amy Adams. Yes, the star,...

Once upon a time, a princess found herself in New York City.

That was the simple but irresistible premise of 2007's Enchanted, which proved to be a star-making role for Amy Adams. Yes, the star,...Source: E! Online (US) - Top Stories | 21 Nov 2024 | 3:00 am

Jennifer Turpin is celebrating a milestone.

Jennifer—who escaped from her parents' "House of Horror" in 2018—shared that she married husband Aron at the Miller Gardens in Rancho Cucamonga, Calif....

Jennifer Turpin is celebrating a milestone.

Jennifer—who escaped from her parents' "House of Horror" in 2018—shared that she married husband Aron at the Miller Gardens in Rancho Cucamonga, Calif....Source: E! Online (US) - Top Stories | 20 Nov 2024 | 10:15 pm

Luke Bryan will be there for Daisy Dove unconditionally.

The American Idol judge revealed that he still keeps in touch with his former costar Katy Perry—who left the singing competition series...

Luke Bryan will be there for Daisy Dove unconditionally.

The American Idol judge revealed that he still keeps in touch with his former costar Katy Perry—who left the singing competition series...Source: E! Online (US) - Top Stories | 20 Nov 2024 | 9:55 pm

Looks like Zach Bryan ditched the red carpet in Nashville for some pink skies.

The “Something In the Orange” singer shared an update on his whereabouts Nov. 20, the same day he was invited to...

Looks like Zach Bryan ditched the red carpet in Nashville for some pink skies.

The “Something In the Orange” singer shared an update on his whereabouts Nov. 20, the same day he was invited to...Source: E! Online (US) - Top Stories | 20 Nov 2024 | 9:43 pm

The future is now for Kim Kardashian.

One day after sharing her meeting with Tesla’s Optimus robot, the Kardashians star posted a moody photoshoot accompanied by another version of the humanoid....

The future is now for Kim Kardashian.

One day after sharing her meeting with Tesla’s Optimus robot, the Kardashians star posted a moody photoshoot accompanied by another version of the humanoid....Source: E! Online (US) - Top Stories | 20 Nov 2024 | 9:15 pm

One of Nickelodeon's most beloved comedy stars has been unmasked as Ice King on The Masked Singer.

An iconic former child star was sent home during the Fox singing competition series' Nov. 20...

One of Nickelodeon's most beloved comedy stars has been unmasked as Ice King on The Masked Singer.

An iconic former child star was sent home during the Fox singing competition series' Nov. 20...Source: E! Online (US) - Top Stories | 20 Nov 2024 | 9:06 pm

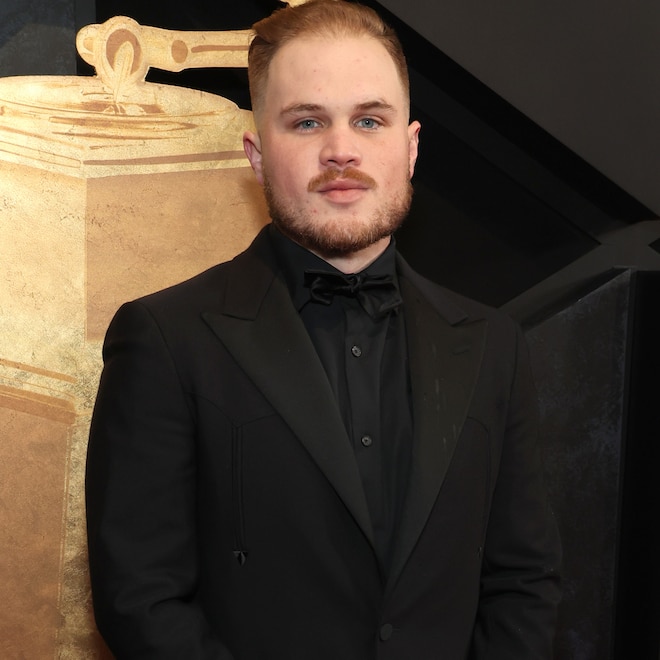

Jelly Roll is suited up and ready to banjo.

The “Son of a Sinner” singer arrived at the Country Music Association (CMA) Awards at Bridgestone Arena in Nashville Nov. 20 alongside his wife Bunnie...

Jelly Roll is suited up and ready to banjo.

The “Son of a Sinner” singer arrived at the Country Music Association (CMA) Awards at Bridgestone Arena in Nashville Nov. 20 alongside his wife Bunnie...Source: E! Online (US) - Top Stories | 20 Nov 2024 | 9:04 pm

We interviewed Bronwyn Newport because we think you'll like her picks. Some of the picks are from Bronwyn's Bedhead PJs collaboration. E! may get a commission if you purchase something through our...

We interviewed Bronwyn Newport because we think you'll like her picks. Some of the picks are from Bronwyn's Bedhead PJs collaboration. E! may get a commission if you purchase something through our...Source: E! Online (US) - Top Stories | 20 Nov 2024 | 9:00 pm

It’s a drag to feel you’re being held hostage by someone else’s nostalgia. The stage show Wicked is beloved by many; it’s been playing on Broadway for 20 years and counting, which means a lot of little girls, and others, have happily fallen under the poppy-induced spell of Winnie Holzman and Stephen Schwartz’s musical about the complex origins of the not-really-so-bad Wicked Witch of the West. Legions of kids and grownups have hummed and toe-tapped along with numbers like “Popular” and “Defying Gravity,” one a twinkly sendup of what it takes to be the most-liked girl at school, the other a peppy empowerment ballad about charting your own course in life. The film adaptation of Wicked—directed by John M. Chu and starring Cynthia Erivo and Ariana Grande—will increase the material’s reach, giving many more people the chance to fall in love with it. Or not.

[time-brightcove not-tgx=”true”]It’s the “or nots” who are likely to be the minority. But if you fail to feel the transformative magic of Chu’s Wicked, there are some good reasons: The movie is so aggressively colorful, so manic in its insistence that it’s OK to be different, that it practically mows you down. And this is only part one of the saga—the second installment arrives in November 2025. Wicked pulls off a distinctive but dismal magic trick: it turns other people’s cherished Broadway memories into a protracted form of punishment for the rest of us.

Read more: Breaking Down Wicked’s Iconic Songs With Composer Stephen Schwartz

Wicked the movie is cobbled together from many complex moving parts, and some of them work better than others. Grande plays Glinda, the good witch of Oz—but is she really all that good? The backstory that will consume all two hours and 41 minutes of this movie—roughly the same amount of time as the stage musical, though again, this is only the first half—proves the almost-opposite. This is really the story of Elphaba, played by Erivo, who is, at the movie’s onset, a reticent young woman with dazzling supernatural powers. The problem is that she has green skin, which makes her a target for mockery and derision, an outcast. Elphaba is a reimagining of the character first brought to life by L. Frank Baum in his extraordinary and wonderfully weird turn-of-the-century Oz books, and later portrayed in the revered 1939 Wizard of Oz by Margaret Hamilton. Wicked—whose source material, roughly speaking, is Gregory Maguire’s 1995 novel Wicked: The Life and Times of the Wicked Witch of the West—is built around the idea that Elphaba wasn’t born bad, but was merely forced into making decisions that set her on a path different from that of the insufferable goody-two-shoes Glinda, her enemy turned frenemy turned friend. The story’s subtext—or, rather, its glaring bold type—is that we’re all shaped by our choices, which are at least partly determined by our response to how others treat us.

But you’ve probably come to Wicked not for its leaden life lessons, but for the songs, for the lavish, showy sets, for the chance to watch two formidable performers parry and spar. Grande brings a not-unpleasant powder-room perkiness to the role of Glinda: as the movie opens, she’s entering Oz’s Shiz University, an institution whose radically uncool name will forever tarnish, sadly, the classic and vaguely scatological phrase “It’s the shizz.” Shiz is the place where kids come to learn magic spells and stuff; Glinda arrives with a million pink suitcases, thinking she’s going to be the star pupil.

Not so fast: Elphaba has also arrived at the school, but not as a student. She’s just there to drop off her younger sister, Nessa Rose (Marissa Bode). Their father, Governor Thropp (Andy Nyman), has hated Elphaba since the day she was born— remember, she’s green and thus different—while doting on Nessa Rose who is, admittedly, so kind and lovely that it’s impossible not to love her. Elphaba, in fact, adores her. And the fact that she uses a wheelchair makes their father all the more overprotective of her. But as Elphaba goes about the business of getting her younger sister settled at Shiz, her fantastical powers—they flow from her like electricity, especially when she’s angry or frustrated—catch the attention of the school’s superstar professor, the chilly, elegant Madame Morrible (Michelle Yeoh). Morrible enrolls Elphaba in Shiz University immediately, making her the unwelcome roommate of Glinda (who is at this point named Galinda, for reasons the movie will explain if you’re curious, or even if you’re not).

Glinda has no use for Elphaba, and goes overboard in making her Shiz experience unbearable. She relegates her roommate to a small, dark corner of their shared quarters and literally crowds her out with mountains of frippery and furbelows, mostly in vibrant shades of pink. In a pivotal scene, she tries to humiliate Elphaba at a school dance and then inexplicably softens; the two become almost-friends. But there’s always an undercurrent of competitiveness there—Glinda isn’t half as gifted as Elphaba is, and she’s the opposite of down-to-earth. Grande has some fun with Glinda’s sugary, over-the-top manipulations: she has the fluttery eyelids of a blinking doll and the twirly elegance of a music-box ballerina. But her shtick becomes wearisome. There’s so much winking, twinkling, and nudging in Wicked that I emerged from it feeling grateful—if only momentarily—for the stark ugliness of reality.

There are so many characters, so many plot points, so many metaphors in Wicked—they’re like a traffic pileup of flying monkeys. Jonathan Bailey plays a rich, handsome prince who, upon his heralded arrival at the school, instinctively likes Elphaba but ends up going steady with Glinda, who practically hypnotizes him into compliance. Jeff Goldblum plays the Wizard of Oz, a lanky charmer who might be a jerk at best and a puppet of fascists at worst. Peter Dinklage provides the voice of a beleaguered professor-goat at the school, Dr. Dillamond. Oz is a community where animals can talk; they’re as intelligent as humans, or more so, and they mingle freely in society. But someone in Oz is seeking to stop all that, launching a campaign to silence all animals, and Dr. Dillamond becomes their unfortunate victim.

Meanwhile, the big message of Wicked—No one is all good or all bad—blinks so assaultively that you’re not sure what any of it means. Metaphorical truisms ping around willy-nilly: It’s OK, even good, to be different! Those who know best will always be the first to be silenced! The popular girl doesn’t always win! It’s tempting to interpret Wicked as a wise civics lesson, a fable for our times, but its ideas are so slippery, so readily adaptable to even the most blinkered political views, that they have no real value. Meanwhile, there are as many song and dance numbers as you could wish for, and possibly more. Chu—also the director of Crazy Rich Asians and In the Heights, both movies more entertaining than this one—stages them lavishly, to the point where your ears and eyeballs wish he would stop.

And yet—there’s Erivo. She’s the one force in Wicked that didn’t make me feel ground down to a nub. As Elphaba, she channels something like real pain rather than just showtune self-pity. You feel for her in her greenness, in her persistent state of being an outsider, in her frustration at being underestimated and unloved. Erivo nearly rises above the material, and not just on a broomstick. But not even she is strong enough to counteract the cyclone of Entertainment with a capital E swirling around her. For a movie whose chief anthem is an advertisement for the joys of defying gravity, Wicked is surprisingly leaden, with a promise of more of the same to come. The shizz it’s not.

Source: Entertainment – TIME | 20 Nov 2024 | 12:32 pm

Charles Manson may have died in 2017, but his story lives on. As one of the most notorious cult leaders and criminals in United States history, Manson was best known for allegedly ordering the “Manson Family Murders” in 1969, where Manson followers Charles “Tex” Watson, Susan Atkins, Patricia Krenwinkel, and Linda Kasabian killed actress Sharon Tate and her unborn child, plus Tate’s visiting friends. The next night, the same group, plus Manson and Family members Leslie van Houten and Steve “Clem” Grogan, drove to the residence of grocery business executive Leno LaBianca and his wife, Rosemary, who were also killed in a similar fashion.

[time-brightcove not-tgx=”true”]Manson and his “Family” have been the subject of countless books, movies, documentaries, and podcasts that examine various angles of the story: Manson’s proximity to the 1960s music scene and countercultural movement, his supposed fixation on “Helter Skelter” (an apocalyptic manifesto for murder adapted from the Beatles’ White Album), and the murder of Tate, who’d been hailed as Hollywood’s next big thing after her starring role in 1967’s Valley Of The Dolls.

Starting Nov. 19, Peacock will contribute another offering to this collection, a three-part docuseries about Manson directed by Billie Mintz (The Guardians). Titled Making Manson, the program features 20 years’ worth of never-before-heard conversions Manson had with pen pal John Michael Jones, who tells filmmakers, “Anything ever written about Manson is contradicted in these tapes.”

Prior to his death, Manson spoke to Jones in-depth about his troubled childhood, growing up abused and a ward of the state of Indiana—with his mother in and out of prison, 9-year-old Manson was sent to the Gibault School for Boys, a Catholic-run school for delinquents in Terre Haute. They discussed various petty crimes and Manson’s early-adulthood prison sentences, and exiting prison during 1967’s Summer of Love at 32. He also spoke to Jones about building his Family (mostly comprising young women whose proper families had disowned them), his aspirations to be a famous musician, and his version of events leading to the Tate-LaBianca murders.

The crux of these recordings, however, is Manson’s own argument that he never technically ordered the murders of Sharon Tate or the LaBiancas and therefore should not have been found guilty of first-degree murder and conspiracy to commit murder in 1971.

In addition to Jones, Making Manson also features interviews with former Family members Dianne Lake, Alan Rose, and Catherine Share, plus journalist Linda Deutsch, Manson’s former cellmate Phil Kaufman, music producer Gregg Jakobson, and forensic psychologist Dr. Tod Roy, among others.

Below is the true story behind the events Making Manson revisits, and the ways in which the tapes complicate the commonly held narratives around Manson’s life and criminal activities.

Read more: 33 True Crime Documentaries That Shaped the Genre

What was Charles Manson’s early life like?

Charles Manson was born in 1934 to a teenage mother and spent most of his early life in correctional institutions. His first imprisonment came in 1951 following a series of robberies and other infractions. In 1956, he was imprisoned at Terminal Island in Los Angeles and McNeil Island in Washington. He was released in 1967 when he was 32 and moved to the Haight-Ashbury District in San Francisco, where he became heavily involved in the hippie movement, taking acid and mushrooms and attending Grateful Dead shows.

Emboldened by the movement’s free love practices, his interest in becoming a famous musician, psychedelic drug use, Biblical teachings, and Beatles songs (among other influences), Manson started preaching his own philosophies and gained a following, primarily of young women who had left home under trying circumstances.

Who is John Michael Jones?

John Michael Jones is a longtime pen pal of Manson’s. Describing himself as a “strung-out junkie” who “lost my business, lost my life,” Jones tells filmmakers how he originally wrote to Manson hoping to get a response including a copy of Manson’s signature to sell online. “It wasn’t that simple, because [Manson] never wrote people,” Jones says. “I knew I had a task in front of me.”

Jones also says he knew that the one thing Manson had been “relentless” about was the fact that he was innocent when it came to ordering the Tate-LaBianca murders in 1969. “I gotta make him think I believe he’s innocent,” Jones tells filmmakers. “So I just wrote this poem about an innocent man sitting on death row in San Quentin… It worked.”

Manson ended up writing Jones back. “Little did I know that searching for an autograph, I was going to walk into a world that I never, ever would have imagined,” Jones says, going on to discuss how Manson “called me out of the blue.” The pair subsequently stayed in touch via phone conversations for a total of 20 years—calls which Manson asked Jones to record.

Their conversations spanned everything from Manson’s abusive upbringing to his “true feelings about the Family” to his self-proclaimed innocence. To be clear, the phone calls do not portray Manson as a good man—something Manson himself made clear from the jump. “All of the other kids wanted to be college professors, I wanted to be a gangster. I wanted to be an outlaw,” he told Jones.

When Manson died in 2017, Jones reportedly set up a GoFundMe to pay for Manson’s burial expenses. GoFundMe shut the page down.

What was “the Family”?

The members of the Manson Family thought of themselves as a hippie commune, but history would come to describe them as a murderous cult. Led by Manson, the Family started in the late 1960s and at its peak included about 100 people, mostly women from middle-class backgrounds who were drawn to the hippie movement’s countercultural ideas and communal living.

As the docuseries lays out, Manson apparently gave his followers a lot of LSD, possibly as a way to manipulate them. By that point, Manson had stopped taking acid but continued to hand it out to the women in his circle. “I never lose control, but I take control,” he tells Jones in the tapes.

Near the end of the ‘60s, the Family was based at the Spahn Ranch in Topanga Canyon—a failing movie set for Westerns-turned weekend rental facility for horses. “There was a lot of sex going on, but it wasn’t a sex cult,” former Family member Catherine Share tells filmmakers.

Share and fellow Family member Dianne Lake (also interviewed for the series) recall moments of physical abuse from Manson, telling filmmakers about being “hit, beat, and raped.” In response, Manson says on tape: “Bunch of kids go around begging and crying about sh-t. I’m protecting my little trip. Doing what any red-blooded American would do.”

What was Manson’s relationship to the Beach Boys and Dennis Wilson?

Prior to settling at Spahn Ranch, Manson and his Family stayed for a period of time at Beach Boys drummer Dennis Wilson’s home on Sunset Boulevard. Manson had learned guitar in prison and had musical aspirations. Wilson developed a close friendship with Manson and introduced him to influential figures in the music industry, such as Columbia Records producer Terry Melcher, who at first expressed interest in signing Manson but quickly changed his mind after witnessing him act out violently. Leaving the Ranch, Melcher told Manson he’d get back to him “real soon” about a record deal, but never did. The fact that Melcher never circled back with Manson was “a real slap in the face,” Catherine Share tells filmmakers. “His code of conduct was that of a convict. And he wore it proudly,” adds Phil Kaufman.

In 1968, Wilson bought a song, “Cease To Exist,” from Manson for $500; the tune later became the Beach Boys’ B-side “Never Learn Not To Love.” Manson was furious that Wilson had changed the song and failed to credit him. According to the recordings, he told Wilson, “Don’t change it. My songs are religion to me, man. He changed it all around, man.” Wilson apparently told Manson not to take it personally, and that this was part of the music industry, which didn’t sway Manson, who felt angry and ripped off.

What was “Helter Skelter”?

“Helter Skelter” was a song from the Beatles’ 1968 self-titled album, also known as the White Album. When Manson heard it, however, he interpreted it as a coded message about an upcoming apocalyptic “race war.”

As Family member Lake recalls to filmmakers: “Charlie played that album frontwards, backwards, and he made us listen to it. He made me stay in the room until I peed my pants so that I would hear it. I think that he really thought that this Black violence was gonna happen. And he wanted us to protect ourselves.”

Manson contradicts this in his tapes, telling Jones: “’Helter Skelter’ wasn’t my trip. That was a f-cking game, man. It was a magical mystery tour.”

What led up to the Tate-LaBianca Murders?

A few Family-related incidents led up to the cult’s most infamous killings.

In the summer of 1969, Family member Charles “Tex” Watson robbed a drug dealer named Bernard “Lotsapoppa” Crowe, who allegedly threatened to kill everyone at Spahn Ranch. Manson responded by shooting Crowe, whom he believed to be a member of the Black Panthers, in the stomach. Crowe, who was not in fact a member of the Black Panthers, survived the shooting.

Still, a paranoid and delusional Manson expected that the revolutionary organization would retaliate, and he brought in the motorcycle gang Straight Satans to act as security at Spahn Ranch. Around this time, he also asked his followers to conduct “creepy crawlies,” in which they would break into homes and move furniture around but not steal anything. According to Share, the Family would do anything for Manson and each other out of a sense of loyalty.

Once the Straight Satans were on board—“They were willing to protect the Ranch because they were getting lots of sex,” Share explains—things went further south with the murder of Gary Hinman.

Who was Gary Hinman?

Gary Hinman was a Topanga resident, UCLA grad student, and part-time music teacher who had occasionally crossed paths with the Manson Family. Journalist and author Ivor Davis tells filmmakers that Hinman also had a side job cooking and selling drugs to make ends meet.

The understanding of the motive behind Hinman’s killing has shifted a bit over the decades. It was initially believed that Manson sent Family members Susan Atkins, Bobby Beausoleil, and Mary Brunner to Hinman’s home to convince him to join the Family, because Manson thought Hinman had inherited about $21,000. (Hinman told the Family that he did not actually have any money.)

Manson, however, told Jones in his tapes that Hinman was killed over a drug deal gone bad. “The Straight Satans wanted mescaline, and Bobby said, ‘I know a friend of mine, Gary Hinman, who sells mescaline. I can get you guys a good deal.’ The Straight Satans said, ‘Hey, this stuff’s no good. We want our money back.’ And Bobby’s like, ‘I can’t. And they’re like, you get us our money back or we’re gonna hurt you.’”

Beausoleil, Brunner, and Atkins ultimately held Hinman captive in his home for two days before Beausoleil stabbed him to death out of fear that he would call the police. Manson also showed up and sliced open Hinman’s ear and cheek with a knife. In an attempt to cover his tracks, Beausoleil wrote “Political Piggy” and drew a panther paw on a wall in blood to make it look like the Black Panthers had committed the crime. Beausoleil was arrested on Aug. 6, 1969, after he was found sleeping in Hinman’s car. There was a bloody knife in the car’s trunk.

In interviews, former Manson friends characterize what happened to Crowe and Hinman as more of a series of bad decisions, as opposed to planned attacks. “We never intended to be violent in any way, shape or form,” Share tells filmmakers. “Charlie was pretty sure that if he didn’t watch out, he was gonna go back to prison.”

Share also theorizes: “Charlie reverted back to his gangster, convict self. I think he had some kind of [psychotic] break and reverted to this mode where he had to do something to get Bobby out of prison.”

“You know, godfather never gets involved in no killing,” Manson says on tape. “I got no blood on my motherf-cking hands, man. I didn’t kill nobody.”

What happened to Sharon Tate and the LaBiancas?

On tape, Manson says Watson “owed” him for getting involved in the Crowe situation. Meanwhile, Manson says he “owed” Beausoleil for preventing Hinman from going to the police. “So I just say, ‘Hey, pay the brother what you owe me.’ I told Tex, ‘Get your brother out of jail.’”

Using “convict’s code,” Manson persuaded Watson and a few other members of the Family to do a copycat murder at the home of Sharon Tate and Roman Polanski, who had gotten married the year before. Then, they should commit another murder at random to look like the Tate murder. “They were going to do whatever it took to free a brother with this insane copycat theory,” says journalist Linda Deutsch to filmmakers.

On Aug. 8, 1969, Watson took Susan Atkins, Patricia Krenwinkel, and Linda Kasabian to 10050 Cielo Drive—a house he and Manson were already familiar with because they’d been to parties hosted by its former tenant, Terry Melcher. Polanski was out of town, but Tate was at home with friends Jay Sebring, Wojciech Frykowski, and Frykowski’s girlfriend Abigail Anne Folger. Also on the property were caretaker William Garretson and his friend Steven Earl Parent. All six adults were killed; Tate was eight and a half months pregnant. The trial included Tate’s unborn child as the seventh murder victim.

The next night, those four Family members plus Manson, Leslie Van Houten, and Clem Grogan drove to Los Feliz in Los Angeles and stopped at 3301 Waverly Drive, where Leno LaBianca lived with his wife, Rosemary. The house was next door to one that had been rented by UCLA graduate student Harold True, and Manson and some Family members had attended a party there the previous year.

In his tapes, Manson claims he walked into 3301 Waverly but left when he realized the LaBiancas were home. “I wasn’t a burglar, I wasn’t causing no trouble. And I backed on out and apologized. And I left,” he says on tape before indicating that Watson chose to stay. “Tex was there, he decided to do what he was doing… Tex was looking for someone to offer up to get a brother out of prison. It didn’t have a f-cking thing to do with what I was doing.” Ultimately, Krenwinkel, Van Houten, and Watson stabbed Rosemary LaBianca 42 times. Watson also stabbed Leno a total of 12 times and carved the word “WAR” into his abdomen.

“Of course, the principal motive for these murders, the main motive, was Helter Skelter, Manson’s fanatical obsession, his mania with Helter Skelter,” lead prosecutor Vincent Bugliosi later theorized in his final statement to the jury. “Helter Skelter was Charlie’s religion, a religion that he lived by. To Manson, Helter Skelter was the Black man rising up against the white man, and then the Black-white war.”

Read more: The 33 Most Anticipated Movies of Fall 2024

What happened to Charles Manson?

In October 1969, the police raided the Manson Family’s new location, Barker Ranch, and arrested its residents on auto theft charges. While in questioning, one member of the group implicated Susan Atkins in the Hinman murder. Later, while in jail, Atkins bragged to her fellow inmates that she’d participated in the Tate-LaBianca murders, which would connect Manson to the crime.

After a media-packed trial, Manson went back to prison in 1971 after being convicted on seven counts of first-degree murder and one count of conspiracy to commit murder. He was originally sentenced to the death penalty, which was overturned the following year when the California Supreme Court ruled that the death penalty was unconstitutional. Manson was re-sentenced in 1977 to life with the possibility of parole. He was denied parole 12 times before his death in 2017 at 83.

What new information do the Manson tapes reveal?

Making Manson attempts to debunk certain infamous theories surrounding the Tate-LaBianca murders, such as “inciting Helter Skelter.” The docuseries also serves up the claim that its namesake had no prior knowledge of the murders themselves. “I’m not saying Manson was an innocent guy,” Jones tells filmmakers. “But Manson was innocent in the sense that he did not order these crimes.”

“I’m not pretending to be good,” Manson says on tape. “They thought that’s what I wanted him to do. I didn’t tell him to do it, because I know better,” he says of Watson. “I know it was a conspiracy if I’d said something. But I didn’t say nothing. I didn’t have nothing to do with killing those people… I thought there was a brotherhood, I stood up for the brotherhood all my life. And when I stood up to the brother with Tex, and Tex went off and did what he did, they blamed me for that. I didn’t tell Tex anything that a marine drill sergeant wouldn’t tell him.

“I don’t go to war with innocent people. I don’t murder people in their beds,” Manson continues, speaking to Jones on tape. “I did other things, but I’m just not guilty of this thing.”

Meanwhile, Watson has always claimed that Manson ordered the murders. In a statement to filmmakers, he says: “My story since the beginning remains the same.” Watson remains in prison; his next parole hearing will be in January 2026.

In addition to claiming that he never explicitly ordered the Tate-LaBianca murders, in his tapes Manson theorizes that many outside factors such as the trial’s media coverage and a “hippie cult leader” narrative painted by lead prosecutor Vincent Bugliosi are to blame for his conviction and cultural infamy. For instance, Manson claims he wasn’t permitted to shave while in jail, so the public would have to see him with an intimidating-looking beard.

Despite Manson’s posthumous protests that he was not guilty of murder or conspiracy to commit murder, former members of the Family, including Share, tell filmmakers they were threatened and intimidated into staying at the ranch while Manson was on trial.

“Charlie threatened me when he was in jail,” Share tells filmmakers. “We went to visit him, then he turned to Clem and he said, ‘if Gypsy [Share’s nickname] tries to leave, I want you to tie her to a car and drag her back to the ranch very slowly. Don’t kill her, but make her wish she was dead.'”

With so many conflicting accounts, including Manson’s, the motives behind the Tate-LaBianca murders remain murky, even as Making Manson attempts to clear them up. One thing appears certain, however: that Manson was a masterful “chameleon,” as many in the docuseries describe him, whose talents lay in getting anyone who crossed his path to do his bidding.

“He’s still lying through his teeth,” Share says about whether to take Manson at his word regarding malice or forethought in the Tate-LaBianca murders.

Concludes forensic psychologist Dr. Tod Roy: “Anybody who came in contact with him ended up hurt or dead.”

Source: Entertainment – TIME | 19 Nov 2024 | 1:01 pm

When Charles Yu was a writer for the dystopian sci-fi HBO series Westworld, he went to set one day and saw dozens of naked actors lying on the floor, playing broken shells of automatons waiting to be revived. “They’re literally bodies lying on metallic shelving—and that’s somebody’s job,” Yu remembers thinking. “They’re coming here to put on body makeup and lie there naked for hours in a 60-degree environment.”

[time-brightcove not-tgx=”true”]Witnessing the fringes of a television set and the stark realities of the people who make a living there partially inspired Yu’s novel, Interior Chinatown, which was released in early 2020. The genre-bending metanarrative tells the story of Willis, a “generic Asian man” in the background of a Law & Order-like procedural who longs to break out of his minor and oft-humiliating role. The novel not only skewered TV’s narrow formulas, but also served as a parable for how Asian Americans have long been shunted to the edges of American society. It struck a nerve during the pandemic, and won the National Book Award for Fiction.

The novel’s breakout success led to Yu receiving an opportunity he had not considered: Hulu calling and asking if he would be interested in turning Interior Chinatown into an actual television series. Such an adaptation would necessitate navigating a head-spinning stack of realities and mediums: to create a police procedural inside of a genre-busting action-dramedy, based on a novel written in the style of a TV screenplay. But Yu jumped at the opportunity, and signed on to write the adaptation and serve as the showrunner. “Going in, I should have been more mindful of the fact that literally everyone was like, this is going to be really hard,” Yu tells TIME. “I didn’t fully understand how hard it would be to crack it until I started doing it.”

Read More: What It’s Like to Never Ever See Yourself on TV

Four years later, the TV adaptation of Interior Chinatown arrives on Hulu on Nov. 19, to positive reviews. Jimmy O. Yang (Love Hard) stars as Willis, alongside Chloe Bennet (Agents of S.H.I.E.L.D.) and Ronny Cheing (The Daily Show), as they attempt to unshackle themselves from their designated societal roles and track down Willis’ long-lost brother. Taika Waititi (Jojo Rabbit, Thor: Ragnarok) executive-produced the show and directed the pilot.

Interior Chinatown is a bit of a paradox: it’s a show whose primary conceit is that Asian-American voices remain on the periphery, while centering an Asian-American everyman hero. This dynamic is not lost on Yu. “I got to make this show, and am an incredibly lucky, privileged person to get to do this,” he says. “But that doesn’t mean I don’t want to tell the story of most people who are not nearly as lucky, including my own parents and a lot of recent immigrants as well.”

In an interview, Yu talked about the state of Asian American representation, recent backlash against diversity initiatives, and the rise of AI. Here are excerpts of the conversation.

TIME: Interior Chinatown was published in early 2020. How did everything that’s happened since impact how you wrote the TV adaptation?

Yu: We started a writers room over Zoom in 2022, and it was really on our minds how the world in which we’d all see each other again would be so different: on the heels of George Floyd, January 6, the wave of anti-Asian sentiment. On one level, the novel is about how Asians are invisible in the American public imagination, which felt more relevant than ever. But I also felt like it could be about so much more, and that it needed to be.

What advice do you have for anyone like Willis, who longs to become the main character of their own story?

Don’t be afraid of looking dumb. I’m 48, and it wasn’t until I became a dad and very cringey that I realized that is something I wish I had been willing to do when I was 28. I was terrified at work: of getting up and talking in front of even five people. So it sounds like such a platitude, but if you’re gonna break out of your role, it starts with you believing you can.

How much did writing for HBO’s Westworld shape Interior Chinatown?

In so many ways. The main thing was that having seen the inside workings of making a TV show, it made me really excited to then start to try to take it apart or poke at it from the inside. It inspired the idea of seeing the edge of the set: The story and then the people behind the story. It gave me that idea that either you’re very, very visible, or you’re completely invisible.

Being on set was surreal. There’s this sense that a lot of the robots are NPCs [non-playable characters], and you may never encounter most of them. Their existence kind of spun me out. What if you’re just a robot who’s off in some dusty side quest, and nobody does your side quest? What is your life like?

Some of the strongest parts of the novel are the characters’ interior thoughts and extensive histories, which they don’t speak out loud. Was it challenging to translate that for TV?

Yeah, that was the single biggest challenge. In a novel you can slip into someone’s consciousness. Gifted filmmakers know how to create subjectivity and interiority, to tell a story that has forward movement but can live in your thoughts and the intimacy of relationships. I learned how to better use silence and negative space.

What did you learn from Taika Waititi, who served as an EP and directed the pilot?

He can take a script and loosen up the connective tissue, to both soften and scuff it up. He’s looking for both visual and emotional nuance: something that’s less polished but much more human.

One of the big conflicts in the book is Willis grappling with whether to climb his way up through an unjust system stacked against him—in which the most he can ever achieve is “Kung Fu Guy”—or to try to rebel from the system itself. Having worked your way up through Hollywood, can you relate?

Oh, that’s a little bit spicy. I’ll try not to duck it. Yes. I’m a rule follower. I started as a good kid of immigrants, who wore a heavy coat of guilt and responsibility: like, ‘Don’t waste our effort.’ I felt like the way I was going to get ahead was working really hard, figuring out the rules of a system, and playing within those rules.

But then I hit a bunch of walls, eventually. And that’s what we see Willis do. Some of the walls are visible and some are not, and a lot of them are internal. I’m not even talking about discrimination, necessarily. I mean, I got to make this show, and am an incredibly lucky, privileged person to get to do this. But that doesn’t mean I don’t want to tell the story of most people who are not nearly as lucky, including my own parents and a lot of recent immigrants as well.

So the parallel is: At some point, you hit the limit of what the rules are going to allow you to to get to, and you have to try things that are scary. There is resistance. No single role is going to define a whole person. That’s what I think the show is ultimately about, for Willis and the other characters: trying on various roles that approximate you but don’t define the totality of what you are.

In 2020, you wrote an essay for TIME about the lack of Asian-American representation on screen. Has anything changed?

There has been noticeable progress, at least from a Hollywood perspective, in the variety and specificity of stories being told. Before, you could list the three Asian things there had been in the last 10 years. Now, there’s kind of too many [to name].

The question is, what do we do with more visibility? What do we do with doors that are now open, that weren’t for a long time?

Amid Donald Trump’s re-election, what do you make of the growing backlash against diversity and inclusion efforts?

Up front, it is important to hear a diversity of voices. But I feel like what I don’t hear in the conversation is empathy, and I include that from my side. I don’t hear a nuanced discussion of why a particular story matters—and I start to hear that hardening into a sort of assumed dogma. Nobody likes to be told that something is important for its own sake.

Now, it’s not some complicated conversation. You can grow up not reading anything about Native Americans or narratives from Black Americans, or not learning about how long Asian Americans have been part of the country. That is a huge problem, because it’s not reality.

But it’s important for us to not devalue the perspective of people who have totally different value systems. The whole point of asking people to read marginalized narratives is so they’ll see the human stories of the people telling them. But that has to go both ways. ‘White guy’ as an epithet is weird to me. I feel like I hear it all the time, and I’m like, ‘Why aren’t we talking as if everyone’s perspective matters, whether or not they look like us?’

Having dealt with AI on Westworld, what do you make of its recent real-world advancements?

It’s weird to have worked on something less than 10 years ago and see that it’s not so sci-fi. I totally believe an AI could write a better rom-com or buddy comedy than I could. But there’s people who have something it’ll be harder to capture, and there’s something magical about that. I don’t think there’s an AI Taika Waititi, for instance.

Source: Entertainment – TIME | 19 Nov 2024 | 10:59 am

Actor and showrunner Natasha Rothwell shares stories about memorable first experiences. Rothwell’s series on Hulu, How to Die Alone, is a first for her too, as both creator and star. How to Die Alone casts Rothwell as Melissa, a self-conscious, self-sabotaging airport worker who has a brush with death during a lonely 35th birthday spent eating takeout and assembling IKEA-like furniture.

Source: Entertainment – TIME | 18 Nov 2024 | 3:38 pm

In 2024, podcasts eclipsed traditional media outlets in their influence over the U.S. election as certain shows with massive audiences managed to score interviews with sought-after subjects trying to widen their reach.

Just look at Vice President Kamala Harris’ decision to talk to Alexander Cooper on Call Her Daddy, a popular podcast known mostly for raunchy sex jokes that crucially attracts young women. Or President-elect Donald Trump’s bro-cast tour on shows like The Joe Rogan Experience that are wildly popular among young men.

[time-brightcove not-tgx=”true”]Read More: Call Her Daddy’s Alexandra Cooper Made Her Name Talking About Sex. Now She’s Pushing Beyond That

Sorry, but you won’t find any of those shows on this best-of list. While some are enjoyable listens, those hosts by definition are not asking our world leaders the hardest questions: That’s why many powerful people prefer to do interviews on those platforms rather than with traditional news outlets.

Still, you will find some of podcasting’s most famous faces—voices?—on this roundup. Call me nostalgic but I found myself seeking out old favorites this fall. Shows I had not listened to for years, like 99% Invisible and Modern Love, experimented with new topics and formats that drew me back into the fold. I eagerly tuned in to new shows from beloved podcasting veterans like Reply All‘s Alex Goldman, Missing Richard Simmons‘ Dan Taberski, or Still Processing‘s Wesley Morris. And the Lonely Island guys did the impossible: Recording a television recap podcast that’s actually funny and worth your time.

Here are the best podcasts of the year.

10. Finally! A Show About Women That Isn’t Just a Thinly Veiled Aspirational Nightmare

As the name might suggest, this audio diary show isn’t about becoming a girl boss or perfecting the high wire act of motherhood. In each episode, a different woman in a particularly fascinating circumstance records a day in her normal life. Some of the more enthralling stories include a recording from an 80-something pinup girl about her time shopping for vibrators and a telehealth abortion provider who works for the intentionally provocative Satanic Temple.

The host-less format is a risk—the episodes don’t have a particular unifying theme or message about womanhood. But we are safe in the hands of two podcasting veterans who know a little something about being a lady: Jane Marie investigated multilevel marketing schemes that target women in The Dream, and Joanna Solotaroff helped produce one of the first breakout comedy podcasts, 2 Dope Queens. The resulting show celebrates women—whatever their specific experiences may be.

Start Here: Finally! A Show About an 83 Year Old Calendar Girl

9. Things Fell Apart

Jon Ronson’s podcast on the culture wars is back for a second season that is even better than the first. Ronson, who wrote Men Who Stare at Goats and So You’ve Been Publicly Shamed among other works, has spent much of the last couple decades chronicling the erosion of our shared notion of truth. Things Fell Apart tries to understand how this fracture occurred by exploring the unlikely origins of major cultural shifts.

Each episode asks a question: How does a serial killer targeting Black sex workers in the 1980s connect to the killing of George Floyd in 2020? How does a bestselling book on trauma fuel campus protests? The stories themselves are engrossing. They take twists and turns that you won’t expect. But the overall effect is chilling.

Start Here: S2. Ep1: The Most Mysterious Deaths

8. My So-Called Midlife

Midlife is often marked by crises, boredom, and restlessness. Reshma Saujani, the founder of Girls Who Code and all-around high-achieving woman, feels ready to blow up her monotonous existence as she stares down 50. On this show, she invites on accomplished women to offer guidance on finding happiness at a challenging time when kids are leaving the home, careers stall, and the body begins to shift.

Saujani takes a few cues from fellow Lemonada podcaster Julia Louis-Dreyfus, who attempts to extract wisdom on aging from women in their 70s and beyond in Wiser Than Me. This show is aimed at a younger demographic and Saujani brings an almost pleading vulnerability to the conversations: She seems to genuinely need guidance on how to endure. Her impressive array of early guests includes Louis-Dreyfus herself, famous economist and parenting guru Emily Oster, and none other than Supreme Court Justice Ketanji Brown Jackson. They offer an array of useful life tips: always find a new way to challenge yourself at work, schedule sex with your partner, and take a 20-minute nap when you’re overwhelmed—in the Safeway parking lot, if you have to.

Start Here: It Could Be F*cking Great With Julia Louis-Dreyfus

7. 99% Invisible: The Power Broker

The preeminent podcast on design—from architecture to clothing to the staging of this year’s Olympics—deserves recognition nearly every year. This year, they decided to celebrate the 50th anniversary of the Pulitzer Prize-winning Robert Moses biography, The Power Broker, with a book club of sorts. Show host Roman Mars and Daily Show writer Elliott Kalan examine Robert Caro’s deep dive into the man who had a greater impact on forming New York City than arguably anybody else in history, inviting guests like New York Times columnist Jamelle Bouie and Rep. Alexandria Ocasio-Cortez to talk about Moses’ legacy.

Under Moses’ supervision, the city built 35 highways, 13 bridges, parks, playgrounds, housing projects, Lincoln Center, Shea Stadium, and the 1964 World’s Fair. But the urban planner also bulldozed through entire neighborhoods to build his ideal city—and doomed New Yorkers to terrible traffic by refusing to expand certain roadways beyond a few lanes. The podcast provides the perfect excuse to finally dip into the 1,200-page tome.

Start Here: The Power Broker #1: Robert Caro

6. Modern Love

The Modern Love Podcast, an adaptation of the beloved New York Times column, has cycled through many formats over the years. Authors have read their essays on love, and so have celebrities. Hosts have conducted conversations with the writers and with readers. In honor of the 20th anniversary of the column, the podcast is yet again trying something new. In a series of recent episodes, host Anna Martin has asked celebrities ranging from Penn Badgley to Samin Nosrat to read essays and then spoken with them about the essays’ amorous themes.

The format works well. It’s rare to hear guarded people open up, but something about reading heart-wrenching piece of writing preps these celebrities for honesty. Several come ready to spill—no one more so than Andrew Garfield, a heart-on-his-sleeve actor whose viral episode brought many to tears. The following episode with Chicken Shop Date host Amelia Dimoldenberg is not quite as vulnerable but equally as intriguing (especially given Garfield and Dimoldenberg’s recent flirtations). You could say I’ve rekindled my relationship with Modern Love.

Start Here: Andrew Garfield Wants to Crack Open Your Heart

5. Empire City: The Untold Story of the NYPD

Chenjerai Kumanyika of Uncivil is back with a show that delves into the history and mythology of the NYPD. That story, inevitably, ties to the evolution of policing in America as a whole. The podcast begins with a disturbing video shot by the NYPD surveilling Kumanyika’s father, a civil right activist. Rewatching the footage inspired Kumanyika to take on this project.

Kumanyika demonstrates how the very foundation of the institution is built on uneven ground: During the Civil War, New York police officers earned payments by kidnapping free Black men and women in the city and shipping them South to be enslaved. He then follows the evolution of the NYPD and the many problematic structural decisions that eroded trust between the police and the people they are sworn to protect. Throughout eight episodes, Kumanyika interweaves personal narrative with rigorous research on the NYPD’s history to make the compelling argument that New Yorkers’ safety isn’t actually the prime objective of the nation’s largest police force.

Start Here: They Keep People Safe | 1

4. Hyperfixed

Reply All was one of the longest-running and most beloved podcasts in the tech space until it imploded in 2022. Since, the two former co-hosts have struck out on their own and, after some experimentation, landed on podcast concepts that are, frankly, extremely similar to Reply All. That’s not a criticism—many people dearly miss the original show.

PJ Vogt’s excellent Search Engine, which answers a wide range of questions about everything from animals in zoos to fentanyl in drugs, has only gotten better since it made my Top 10 list last year. Now comes Alex Goldman’s Hyperfixed, a help desk podcast that riffs on Reply All’s “Super Tech Support” segment. Goldman bills himself as an“overconfident idiot” all too eager to help with random problems that unfold in unexpected ways. An episode on a New Yorker who needs Goldman’s help getting her driver’s license expands into an investigation into why driving in New York is awful. An entry on perfecting a baking recipe diverts into the confounding history of the U.S. refusing to implement the metric system and an interview with award-winning chef Nancy Silverton. Though Goldman has only produced two episodes so far, the series proved immediately addictive and charming. I’m betting I’ll become a regular listener.

Start Here: Eva Needs to Measure

3. The Wonder of Stevie

As a dedicated listener to both Do You Like Prince Movies? from Grantland and Still Processing from the New York Times, I would tune in to just about anything Pulitzer Prize-winning cultural critic Wesley Morris creates. Morris formerly co-hosted those shows with other writers. The Wonder of Stevie is a different endeavor, an overview and deep analysis of the career of an iconic musician that Morris tackles solo, though he occasionally gets a helping hand from none other than former President Barack Obama. Morris interviews the likes of Questlove, Janelle Monae and Michelle Obama about Stevie Wonder’s career. (The Obamas’ Higher Ground helped produce the podcast.)

The podcast begins in 1972. Over the next five years, Wonder produced five albums and won half a dozen Grammys, one of the most impressive runs in music history. Even if you don’t care about Wonder, you should care about what Morris cares about: He is always able to succinctly divine meaning from great art. And this podcast in particular is a joyful celebration. He also heroically moderates a conversation in the final episode between Barack Obama and Stevie Wonder himself.

Start Here: Music of My Mind | 1972

2. The Lonely Island & Seth Meyers Podcast

Typically, podcasts that involve celebrities recapping their own shows tend to be self-indulgent, un-analytical, and not particularly revealing. But I fell hard for The Lonely Island & Seth Meyers Podcast. Each episodes focuses on a different Lonely Island Saturday Night Live sketch. Andy Samberg, Jorma Taccone, and Akiva Schaffer offer insight into the stressful yet hilarious process of writing joke songs about d—cks in boxes with Justin Timberlake and coming up with swear words for Natalie Portman to rap.

It’s a cliche to praise podcasts for effortless chemistry, but it should be no surprise that a trio that has worked together for decades on songs like “I’m on a Boat” and movies like Pop Star have it. (So does Meyers, who apparently is in a daily text exchange with Samberg about their Spelling Bee scores.) The podcast serves up unabashedly nostalgic content for those of us who came of age in the late 2000s, but it also lands at an existential moment for SNL on the eve of its 50th anniversary. Some 20 years ago, Lonely Island dragged SNL into the YouTube era and set trends that persist on TikTok today. Perhaps there are lessons to be gleaned from this throwback show for the future of comedy.

Start Here: Lazy Sunday

1. Hysterical

The most engrossing podcast Dan Taberski has produced since Missing Richard Simmons, Hysterical investigates a mysterious illness that spread among high school girls randomly exhibiting Tourette’s-like symptoms about a decade ago in Le Roy, New York. The incident is believed to be the largest case of mass hysteria since the Salem Witch Trials. The show explores the origins of hysteria, other modern examples, and what patients do when confronted with the frustrating diagnosis that their symptoms are “all in their head.”

While the history of hysteria is intriguing, Hysterical is at its strongest when Taberski is speaking with the women who were once afflicted by what they argue was a mysterious—but very real—illness. The scandal occurred near Taberski’s hometown in upstate New York, and he’s able to bring a local charm to his color commentary and interviews. He manages to make what might feel like a dour show on a serious topic feel light and brisk.

Start Here: Outbreak | 1

Source: Entertainment – TIME | 18 Nov 2024 | 11:00 am

Warning: This post contains spoilers for Episode 1 of Dune: Prophecy.

Set 10,000 years before the birth of Paul Atreides and his rise as the prophesied messiah known as Lisan-al-Gaib, HBO’s new Dune: Prophecy series chronicles the early evolution of the Bene Gesserit order from a fledgling school for gifted young women to the superpowered mystical sisterhood that’s pulling the strings of the imperial government at the start of Dune.

[time-brightcove not-tgx=”true”]Dune: Prophecy is based on 2012’s Sisterhood of Dune, the first book in the Great Schools of Dune prequel trilogy written by Brian Herbert, the son of Dune author Frank Herbert, and Kevin J. Anderson following Frank’s death. Showrunner Alison Schapker’s series centers on Harkonnen sisters Valya and Tula (played as adults by Emily Watson and Olivia Williams and in flashbacks by Jessica Barden and Emma Canning). Born approximately 60 years after the end of the great machine wars known in the Dune universe as the Butlerian Jihad—a crusade by the last free humans in the universe that wiped out all machine-based technology—the sisters are distant ancestors of the Baron Vladimir Harkonnen, his nephews, Feyd-Rautha and Beast Rabban, and, as was revealed in the Dune Part II movie, Paul’s mother Jessica and Paul himself.

As the Imperium’s history books tell it, House Atreides forerunner Vorian Atreides led the humans to victory over the machines during the final days of the wars while Valya and Tula’s great-grandfather, Abulard Harkonnen, deserted the fight and was branded a coward. This resulted in House Harkonnen being disgraced and exiled to the desolate planet of Lankiveil. However, Valya contends that the history the Atreides wrote was built on lies and resolves at a young age to upend the status quo by gaining power through the Bene Gesserit.

A rift within the sisterhood

When we’re introduced to Valya and Tula as young siblings in Prophecy‘s premiere, Valya is being primed as the successor to the Bene Gesserit’s first-ever Mother Superior, Raquella Berto-Anirul (Cathy Tyson), in place of Raquella’s own granddaughter, Reverend Mother Dorotea (Camilla Beeput). Raquella, who was a hero during the wars, originally founded the order to train its members to work as Truthsayers, those who could wield the power of truthsense and be assigned to the Great Houses to help them sift truth from lies.

However, as an older Valya explains in a voiceover, at that time, there was contention in the Bene Gesserit ranks over Raquella’s desire to create a secret breeding program that the sisterhood could use to foster the right royal unions and cultivate rulers the Bene Gesserit could control. While Valya was of the same mind as Raquella, Dorotea, whom Valya refers to as a “zealot,” viewed the breeding program as heresy and believed the order was meant to guide the Imperium, not rule it. (This is the same breeding program the Bene Gesserit are using 10,000 years later to try to achieve their goal of producing the chosen one known as the Kwisatz Haderach, an unparalleled Bene Gesserit male capable of accessing all of his ancestral memories and seeing all possible futures.)

After summoning Valya to her side on her deathbed, Raquella relays a prophecy that makes Valya even more firm in her beliefs. “Red dust. It’s coming. Titan-Arafel,” she says, using a phrase that refers to a reckoning in the form of a holy judgment brought on by a tyrant. “You will be the one to see the burning truth and know.”

When Dorotea then attempts to destroy the breeding index despite her grandmother’s final words, Valya uses a new ability she’s been cultivating called the Voice—a skill that allows the user to speak in such a way that another person must obey anything they say—to force Dorotea to kill herself with her own blade.

Mother Superior Valya Harkonnen

As the inventor of the Voice and Mother Superior Raquella’s protégée, Valya is the natural heir to the Bene Gesserit’s top position once Dorotea is out of the way. And 30 years later, it’s clear she’s progressed the order’s hold on the Imperium quite extensively.

Having schemed for Princess Ynez (Sarah-Sofie Boussnina), the daughter of Emperor Javicco Corrino (Mark Strong) and heir to the Imperial throne, to come study to become a sister following her arranged marriage to the child heir of House Richese, 9-year-old Pruwet Richese (Charlie Hodson-Prior), Valya is close to achieving her goal of setting up one of the Bene Gesserit’s own to rule as the first-ever empress of the Imperium. That is, until the death of Pruwet—as well as House Corrino’s truthsayer, Reverend Mother Kasha (Jihae)—at the hands of Desmond Hart (Travis Fimmel). Desmond, a previously-presumed-dead soldier in Emperor Corrino’s army who returns from serving on the desert planet Arrakis claiming he has been gifted a “great power,” signals to Valya that “the burning truth” Raquella spoke of is finally being revealed.

“[Desmond is] tied to the prophecy that sort of sparks the series,” Schapker told IGN. “He really is a mystery of the show. And who has empowered him or what has empowered him is a central mystery that our sisters have to find out.”

The remaining five episodes of Dune: Prophecy will air weekly on HBO at 9 p.m. ET on Sundays, the same time they become available to stream on Max.

Source: Entertainment – TIME | 17 Nov 2024 | 10:07 pm

Warning: This post contains spoilers for the first episode of Dune: Prophecy.

The HBO series Dune: Prophecy is set about 10,000 years before the birth of Paul Atreides, the protagonist of the original Dune books. Sadly, that means Timothée Chalamet—who plays Paul in Denis Villeneuve’s ongoing adaptation of Frank Herbert’s Dune novels—won’t be making any cameos as a hot prophet in the six-episode season. But the good news is his ancestors play a big role in the show, as do the ancestors of Paul’s rival, Feyd-Rautha Harkonnen (played by an eyebrow-less Austin Butler in Dune: Part 2) and those of his betrothed, Princess Irulan (Florence Pugh, who looked regal for the 7 minutes and 47 seconds she was onscreen in the Dune sequel).

[time-brightcove not-tgx=”true”]Dune: Prophecy is loosely based on the novel Sisterhood of Dune, co-written by Frank Herbert’s son, Brian Herbert, and Kevin J. Anderson. The show centers on Valya Harkonnen (Jessica Barden and later Emily Watson), who joins a cult of witches and eventually earns the title Mother Superior of the Sisterhood. The Sisterhood will eventually become the Bene Gesserit, the mystical clan to which Paul’s mother Jessica (Rebecca Ferguson) belongs.

Read More: Breaking Down the Complex Family Tree in the Dune Universe

Valya is not a good person. We see early in the show that she uses the Voice—a deep, foreboding register that she can summon in order to force people to do her bidding—to make a fellow Sister slit her own throat. But what did you expect? Her descendants are creepy, hairless dudes who torture people for fun.

Still, Dune: Prophecy does try to conjure up some sympathy for the Harkonnens, who, according to their own family mythology, were unjustly condemned by an Atreides and then banished to a barren ice world. They’re doomed to sell smelly whale meat for a living.

If the Atreides-Harkonnen feud sounds familiar, that’s because it’s a key plot point in the two Dune movies. Giant slug-man Baron Vladimir Harkonnen (an unrecognizable Stellan Skarsgård) tortured the noble Duke Leto Atreides (Oscar Isaac, naked for some reason) in Dune: Part 1. And Paul Atreides and Feyd-Rautha Harkonnen engage in a West Side Story-esque rumble in Dune: Part 2.

Now, you may be wondering, how is it that this family feud has persisted across 10 millennia?Apparently little has changed in the Imperium between the events of Dune: Prophecy and Dune. Mark Strong plays Emperor Javicco Corrino in Dune: Prophecy, and it’s his line that will eventually produce Christopher Walken’s Emperor Shaddam Corrino IV and Pugh’s Princess Irulan Corrino. Arrakis remains a terrifying yet coveted planet because it is home to the precious resource of Spice. Even the shield technology that soldiers deploy when fighting is identical. Sure, the characters in Dune are scared of “thinking machines” or A.I. But, for perspective, the fall of Rome was just 1,548 years ago. And 10,000 years ago was the end of the Ice Age. (For technology, the ruling family, or even the outfits to have not changed in 10 millennia in the Dune universe is a bit mind-boggling. But I digress!)

Read More: A Dune Family Tree to Help Explain That Part Two Surprise Reveal

The fact that the Atreides-Harkonnen feud has persisted from the time of Dune: Prophecy to Dune suggests that the rivalry is essential to Herbert’s universe. Yet the origins of the rift go largely unexplained in Herbert’s original series. Characters reference that it began during a great war but don’t dive into the details. Here’s the background of the Harkonnen-Atreides rivalry.

The original Dune book offers only hints about the origin of the feud

Lady Jessica briefly alludes to the origins of this blood feud in the pages of Frank Herbert’s Dune upon which Villeneuve’s movies are based. As a political power struggle builds between the Atreides and the Harkonnen families, Jessica observes, “The Harkonnens won’t rest until they’re dead or my Duke destroyed… The poison in [Baron Harkonnen], deep in his mind, is the knowledge that an Atreides had a Harkonnen banished for cowardice after, the Battle of Corrin.”

That’s pretty much all that Frank Herbert says on the matter. We never find out the details of the cowardly act. Frank Herbert’s son, Brian Herbert, carried on his legacy and wrote books set in the Dune universe, including one titled The Battle of Corrin. Many Dune fans do not consider Brian Herbert’s books canon. But some of his stories are the loose basis for Dune: Prophecy, so they’re probably worth summing up here, whatever their literary merit.

What went down at the Battle of Corrin

According to Brian Herbert, many millennia before the events of Dune, humans were enslaved by A.I. (Think: Terminator or The Matrix or Battlestar Gallactica…or really any sci-fi property written in the last century.)

A group of human rebels rose up against what are called the “thinking machines.” A guy named Vorian Atreides lead humanity’s army in the last battle on the planet of Corrin. There, the machines held two million humans captives in cargo containers that were rigged to explode as soon as the human military advanced.

Read More: How the Ending of Dune: Part Two Sets Up a Third Movie

Hundreds of billions (yes, I said billions) of humans had already died in the war. Vorian argued they ought to sacrifice the two million hostages to end the conflict. But Bashar Abulurd Harkonnen, who served under Vorian, disagreed. The two argued and Vorian dismissed Abulurd. Abulurd, in an attempt to save the captives, disarmed the weapons of the entire human fleet, crippling them in their fight against he machines.

Abulurd’s betrayal resulted in an extremely bloody battle. At the end of the war, Vorian branded Abulurd a coward, and the Imperium banished him to a desolate planet where his family could eke out a living selling whale meat. Which, again, is a bit grim.

Where the Harkonnens and Atreides stand at the time of Dune: Prophecy

Many Dune fans consider the above explanation for the feud non-canonical, but it does seem to be the basis for Valya’s grudge in Dune: Prophecy. Valya speaks about her family legacy with a disturbing intensity through the first episode of the series. She also cites restoring her family’s honor as the reason she murdered another woman in the Sisterhood.

Read More: Why Filmmakers From David Lynch to Denis Villeneuve Have Struggled to Adapt Dune

In a vacuum, Valya’s actions seem, frankly, unhinged. But she believes Abulurd acted as a hero, not a coward and resents his fall. Though the shaming of her great-grandfather doesn’t excuse her willingness to lie and murder her way to becoming Mother Superior of the Sisterhood, it does add context for why she is so ruthless in her goal to restore the family’s honor.

Valya’s seething hatred for the Atreides clan does not bode well for Keiran Atreides (Chris Mason), the swordmaster to the Emperor, and the only Atreides audiences have met so far on the show. Valya is almost certainly aware of his presence in the Emperor’s court and perhaps even aware that he has been flirting with Princess Ynez Corrino (Sarah-Sofie Boussnina).

Keiran, for his part, seems more interested in seducing the princess than he does in engaging with Valya’s vendetta—at least for now.

Source: Entertainment – TIME | 17 Nov 2024 | 10:06 pm

You may recognize the names of the main players in HBO’s Dune prequel series, Dune: Prophecy. Frank Herbert’s Dune books and the film adaptations by Denis Villeneuve center on Paul Atreides, a prophet of sorts plagued by his calling to overthrow the galactic order. Paul spends most of the first Dune novel avenging the death of his father at the hands of a villain named Baron Harkonnen and the Emperor Shaddam Corrino IV, both of whom believe Paul’s family to be a threat to their power.

[time-brightcove not-tgx=”true”]Dune: Prophecy is set 10,000 years before the birth of Paul. But somehow the names and even system of government are familiar. The Corrino family rules the Imperium. The Harkonnens and Atreides are still rivals and major players in the galaxy’s political realm. The line of the Emperor in Dune: Prophecy, Javicco Corrino, will eventually produce Emperor Shaddam Corrino IV. Keiran Atreides is related to Paul. And Valya Harkonnen, the main character in Prophecy, will eventually link to Paul’s rival Feyd-Rautha Harkonnen.

Read More: Denis Villeneuve’s Take on Dune Is an Admirably Understated Sci-Fi Spectacle

Here is how the characters in Dune: Prophecy relate to those in Dune.

The Corrino Family in Dune: Prophecy

When the series begins, Emperor Javicco Corrino (Mark Strong) rules over the Imperium. He and his wife, Empress Natalya Arat Corrino (Jodhi May), have two children: Constantine Corrino (Josh Heuston) and Ynez Corrino (Sarah-Sofie Boussnina). Ynez, the older of the two, is betrothed to a (very) young man and plans to train with the Sisterhood to become a Truthsayer while she waits for her fiancé to grow up.

The Harkonnen Family in Dune: Prophecy

Mother Superior Valya Harkonnen (Jessica Barden, and then Emily Watson) is the protagonist of Dune: Prophecy. She runs the Sisterhood, which will eventually become the Bene Gesserit, with the support of her actual sister, Reverend Mother Tula Harkonnen (Emma Canning, and then Olivia Williams).

Valya often speaks of restoring the Harkonnen family name. According to the Dune prequels written by Frank Herbert’s son, Brian Herbert, long before Valya was born, the peoples of the Dune series were enslaved by A.I. Humanity rose up against the machines and after about a century of fighting and the deaths of billions of humans, a man named Vorian Atreides endeavored to lead an army to take down the machines, once and for all, at the Battle of Corrin.

Read More: Why Filmmakers From David Lynch to Denis Villeneuve Have Struggled to Adapt Dune

The machines held two million humans captive, and Vorian decided he was willing to sacrifice those hostages in order to end the war. Bashar Abulurd Hakronnen, a soldier who served under Vorian, disagreed. He disabled the humans’ weapons in hopes of saving the hostages. The result was a bloody battle that ended many lives. Aftewards, Vorian branded Abulurd a traitor, and Abulurd was banished to an ice planet.

Valya, Abulurd’s great-granddaugther, believes that Abulurd was doing something heroic, not cowardly. She vows to restore the Harkonnen family name and seek vengeance against the House of Atreides.

The Atreides Family in Dune: Prophecy

The only member of the Atreides family that we meet in Dune: Prophecy is Keiran Atreides (Chris Mason), the sword master for the emperor and his family. Currently Keiran seems to be spending as much time flirting with Princess Ynez as he is thinking about his family legacy.

The Corrino Family in Dune

Ten millennia have passed between the events of Dune: Prophecy and Dune. And yet, somehow, the Corrino family is still in power. Emperor Shaddam Corrino IV (Christopher Walken in the Denis Villeneuve movies) rules over the Imperium in Dune. He is attended to by his daughter, Princess Irulan Corrino (Florence Pugh), a Bene Gesserit whose writing appears in the Dune books.

Shaddam fears Duke Leto Atreides’ popularity and helps Baron Vladimir Harkonnen kill Leto by lending the Harkonnens the royal family’s elite military force, the Sarduakar. Paul Atreides eventually avenges his father by rallying the Freman of the Desert Planet Arrakis to his cause, killing all the Harkonnens, and securing his spot as leader of the Imperium by betrothing himself to Princess Irulan.

The Harkonnen Family in Dune

The Harkonnen family of this era is led by Baron Vladimir Harkonnen. Baron Harkonnen believes that he has no children and names Feyd-Rautha, the son of his half-brother as heir to the family legacy. He also deploys his half-brother’s other son, Glossu Rabban, known as Beast, in battle.

Unbeknownst to the Baron, he did sire a child. That girl grew up to be Lady Jessica, who became the concubine of Duke Leto Atreides and birthed Paul and Alia. That means that Baron Harkonnen is technically Paul’s grandfather.

Read More: How the Ending of Dune: Part Two Sets Up a Third Movie

The Bene Gesserit hid Jessica’s parentage from her and initially instructed her when she became pregnant to ensure she gave birth to a girl. The cult’s plan was to marry the female Atreides heir to Feyd-Rautha, and together they would birth the Kwisatz Haderach, or Chosen One. But instead, Jessica used her powers to ensure her first born was a boy.

The Atreides Family in Dune

Duke Leto Atreides is the pater familias of the Atreides clan in Dune. He and Lady Jessica had two children, Paul and Alia, though Alia was born after Leto had died. Paul is believed by many to be the Kwisatz Haderach and is able to wield special powers, though he doubts his status as the so-called chosen one throughout the story. His status as a hero or a villain comes into question as the story wears on. Alia, too, wields special powers even from the time she is in utero.

Source: Entertainment – TIME | 17 Nov 2024 | 10:37 am

ARLINGTON, Texas — The boos from a crowd wanting more action were growing again when Jake Paul dropped his gloves before the final bell and bowed toward 58-year-old Mike Tyson.

Paying homage to one of the biggest names in boxing history didn’t do much for the estimated 72,000 fans who filled the home of the NFL’s Dallas Cowboys on Friday night.

[time-brightcove not-tgx=”true”]Paul won an eight-round unanimous decision over Tyson as the hits didn’t match the hype in a fight between the 27-year-old YouTuber-turned-boxer and the former heavyweight champion in his first sanctioned pro bout in almost 20 years.

All the hate from the prefight buildup was gone, replaced by boos from bewildered fans hoping for more from a fight that drew plenty of questions about its legitimacy long beforehand.

The fight wasn’t close on the judge’s cards, with one giving Paul an 80-72 edge and the other two calling it 79-73.

“Let’s give it up for Mike,” Paul said in the ring, not getting much response from a crowd that started filing out before the decision was announced. “He’s the greatest to ever do it. I look up to him. I’m inspired by him.”

Tyson came after Paul immediately after the opening bell and landed a couple of quick punches but didn’t try much else the rest of the way.

Even fewer rounds than the normal 10 or 12 and two-minute rounds instead of three, along with heavier gloves designed to lessen the power of punches, couldn’t do much to generate action.

Paul was more aggressive after the quick burst from Tyson in the opening seconds, but the punching wasn’t very efficient. There were quite a few wild swings and misses.

“I was trying to hurt him a little bit,” said Paul, who is 11-1 with seven knockouts. “I was scared he was going to hurt me. I was trying to hurt him. I did my best. I did my best.”

Tyson mostly sat back and waited for Paul to come to him, with a few exceptions. It was quite the contrast to the co-main event, another slugfest between Katie Taylor and Amanda Serrano in which Taylor kept her undisputed super lightweight championship with another disputed decision.

Paul, who said an ankle injury limited his sparring sessions in the final weeks of training camp, said he eased up starting in about the third round because he thought Tyson was tired and vulnerable.

“I wanted to give the fans a show, but I didn’t want to hurt somebody that didn’t need to be hurt,” Paul said.

It was the first sanctioned fight since 2005 for Tyson, who fought Roy Jones Jr. in a much more entertaining exhibition in 2020. Paul started fighting a little more than four years ago.

“I didn’t prove nothing to anybody, only to myself,” Tyson said when asked what it meant to complete the fight. “I’m not one of those guys that looks to please the world. I’m just happy with what I can do.”

The fight was originally scheduled for July 20 but had to be postponed when Tyson was treated for a stomach ulcer after falling ill on a flight. His record is now 50-7 with 44 knockouts.

Tyson slapped Paul on the face during the weigh-in a night before the fight, and they traded insults in several of the hype events, before and after the postponement.

The hate was long gone by the end of the anticlimactic fight.

“I have so much respect for him,” Paul said. “That violence, war thing between us, like after he slapped me, I wanted to be aggressive and take him down and knock him out and all that stuff. That kind of went away as the rounds went on.”

The fight set a Texas record for combat sports with a gate of nearly $18 million, according to organizers, and Netflix had problems with the feed in the streaming platform’s first live combat sports event. Netflix has more than 280 million subscribers globally.

“This is the biggest event,” Paul said. “Over 120 million people on Netflix. We crashed the site.”

Among the celebrities on hand were basketball Hall of Famer Shaquille O’Neal and former NFL star Rob Gronkowski, along with Cowboys owner Jerry Jones.

Evander Holyfield and Lennox Lewis, two foes from Tyson’s heyday, greeted him in his locker room before the fight.

Tyson infamously bit Holyfield on the ear in a 1997 bout, and he appeared to have one of his gloves in his mouth several times during the Paul bout. He was asked if he had problem with his mouthpiece.

“I have a habit of biting my gloves,” Tyson said. “I have a biting fixation.”

“I’ve heard about that,” the interview responded.

According to reports, Paul’s payday was $40 million, compared with $20 million for Tyson. Paul mentioned his number during a promotional event over the summer. Tyson has a history of legal and financial troubles but had said he didn’t take the fight for money.

Mario Barrios retained the WBC welterweight title in a draw with Abel Ramos on the undercard. Barrios was in control early before Ramos dominated the middle rounds. Each had a knockdown in the 12-round bout.

It was the first fight for the 29-year-old Barrios since he was appointed the WBC welterweight champ when Terence Crawford started the process of moving up from the 147-pound class.

Barrios, who is 29-2-1, won the interim WBC title with a unanimous decision over Yordenis Ugás last year. The 33-year-old Ramos is 28-6-3.

Source: Entertainment – TIME | 16 Nov 2024 | 9:00 am